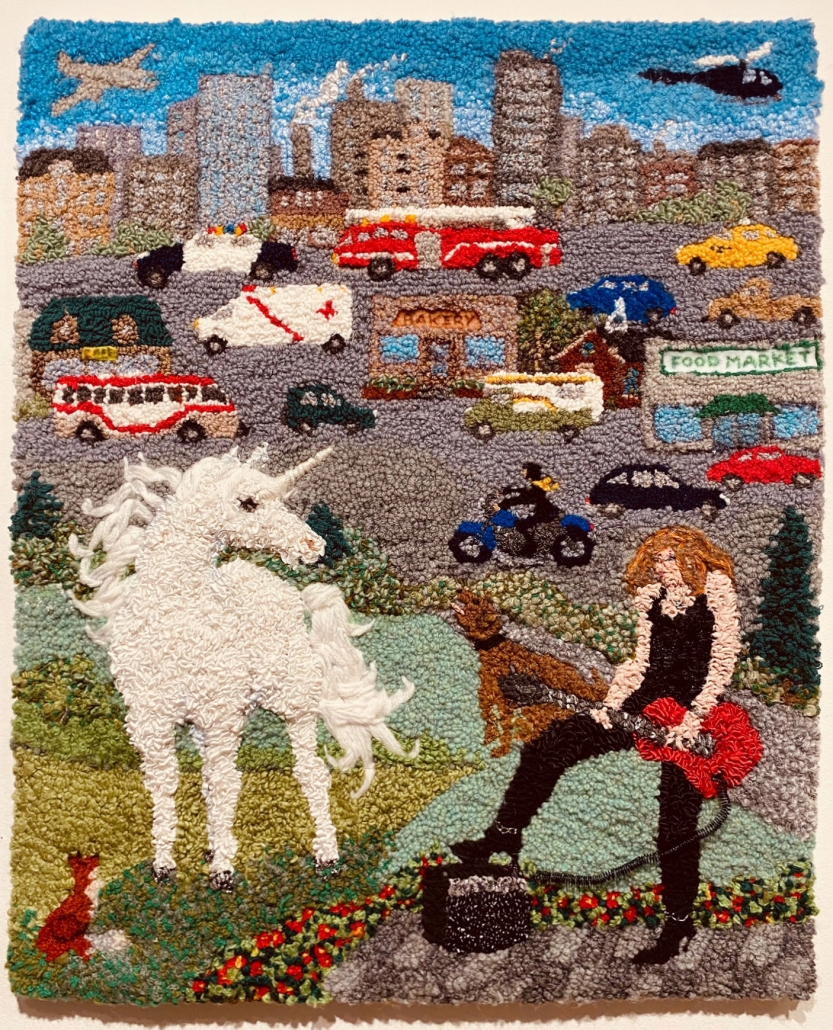

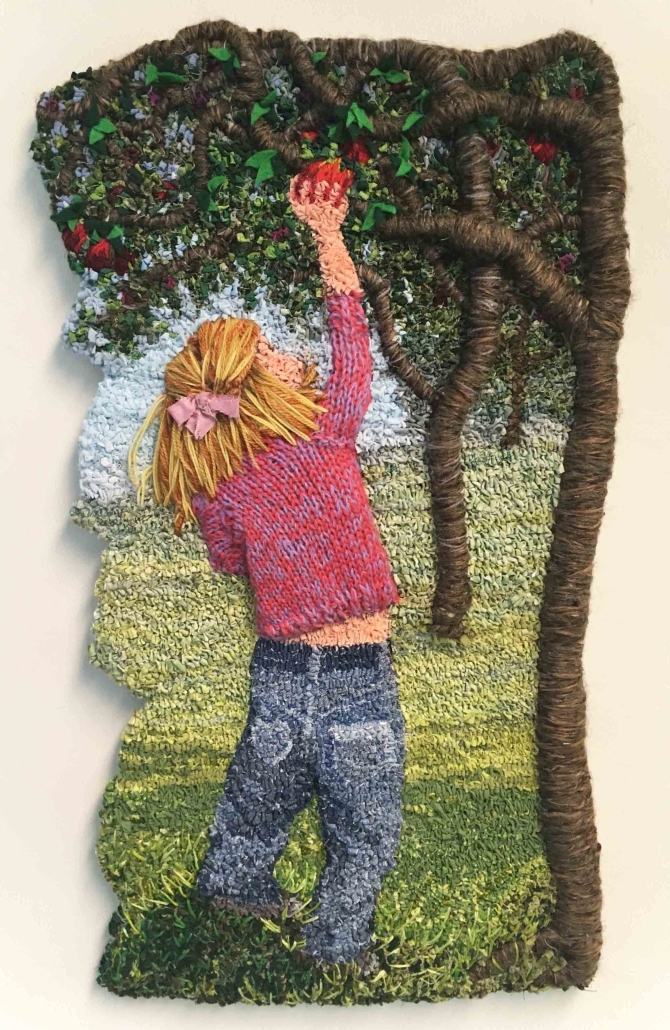

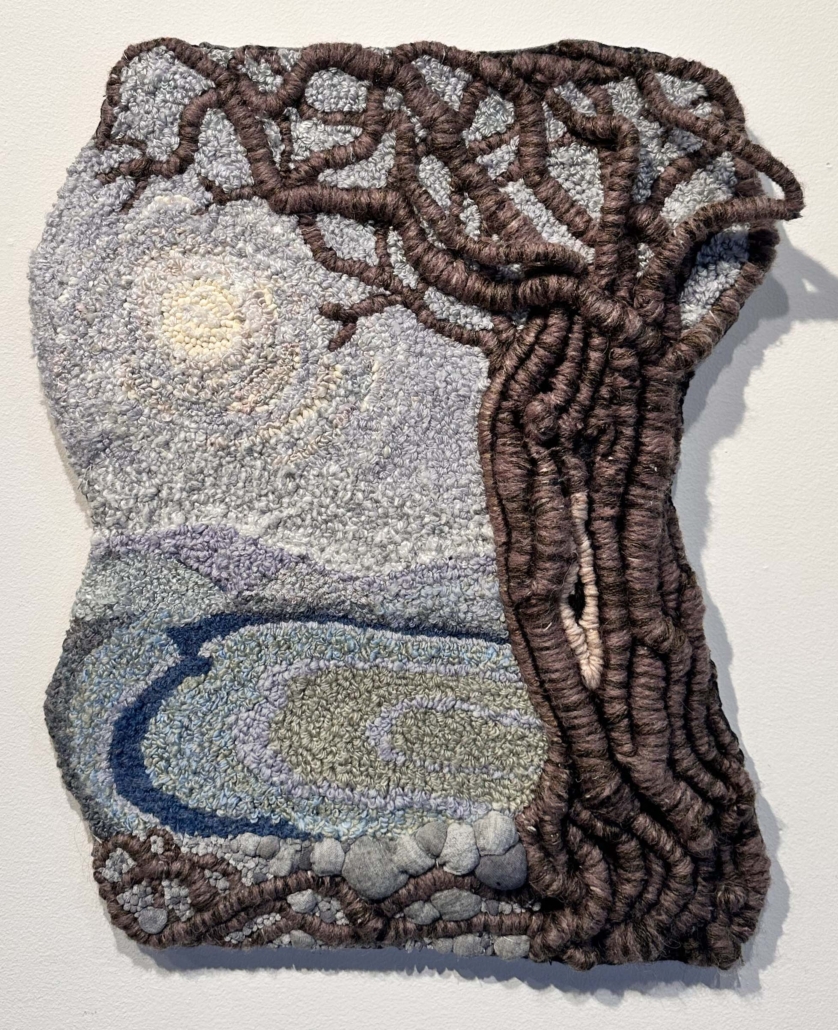

THE ART OF Sharon (Sharden) Johnston

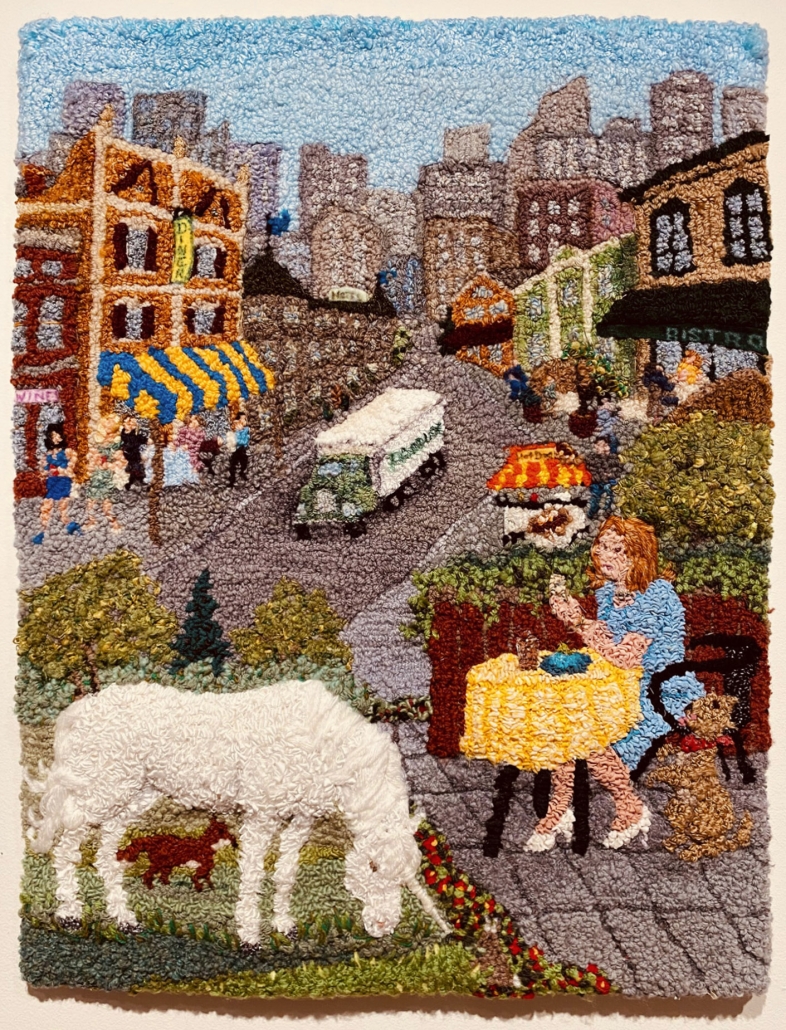

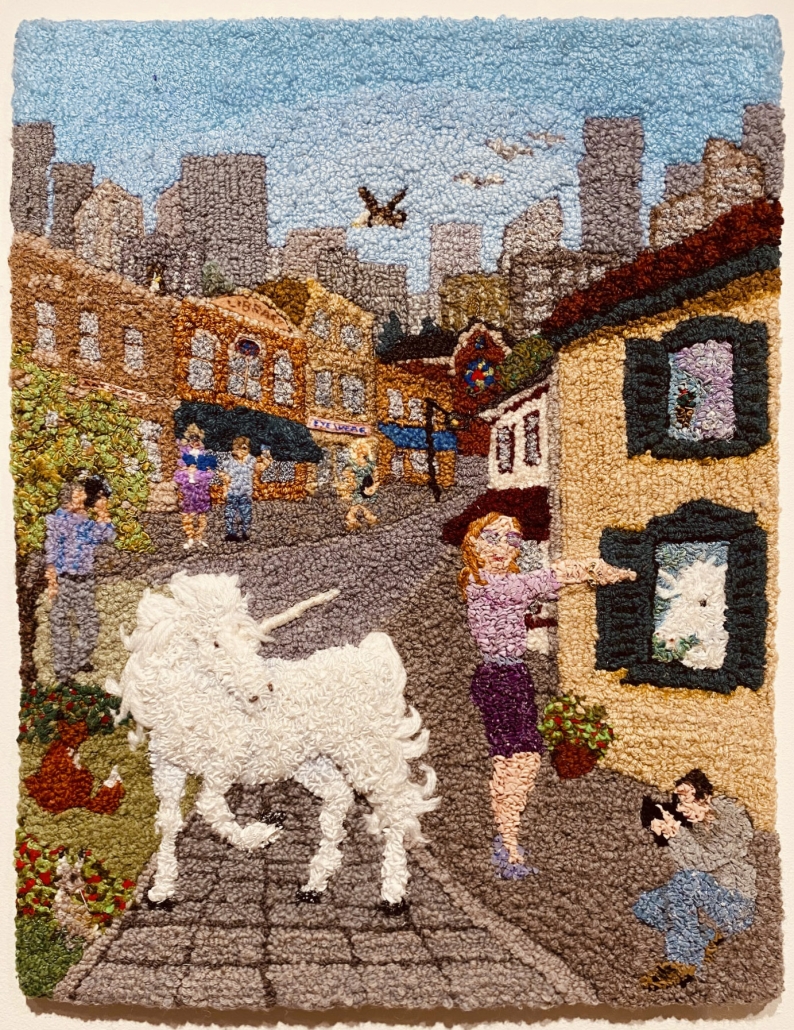

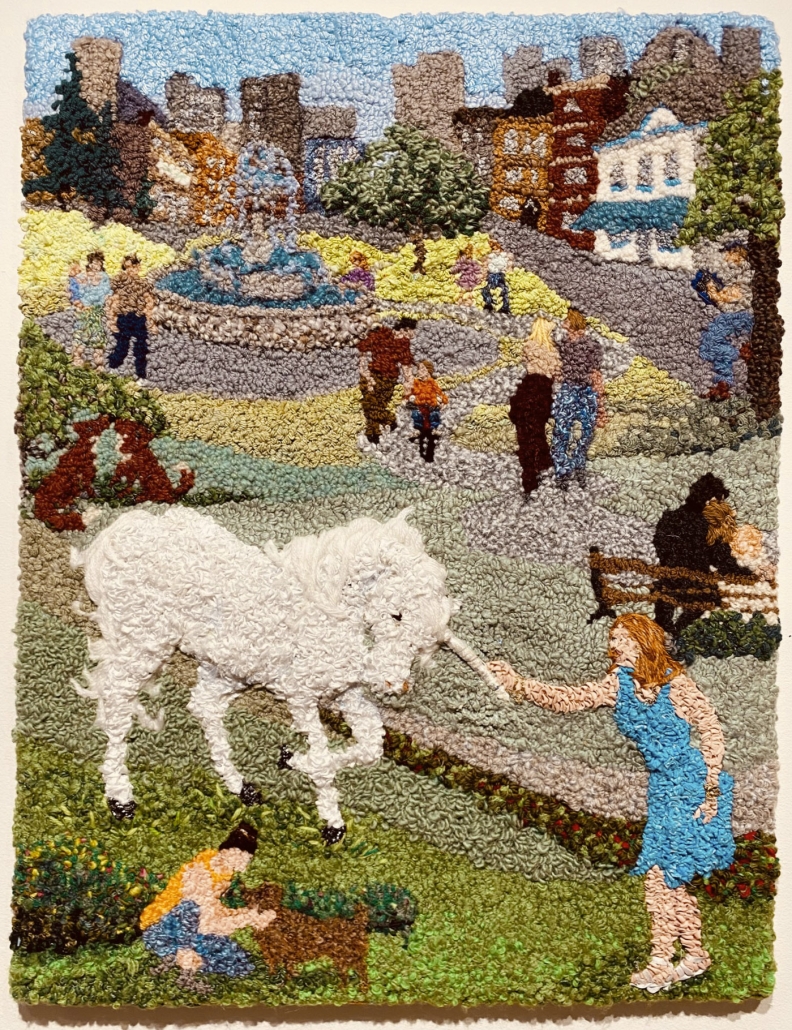

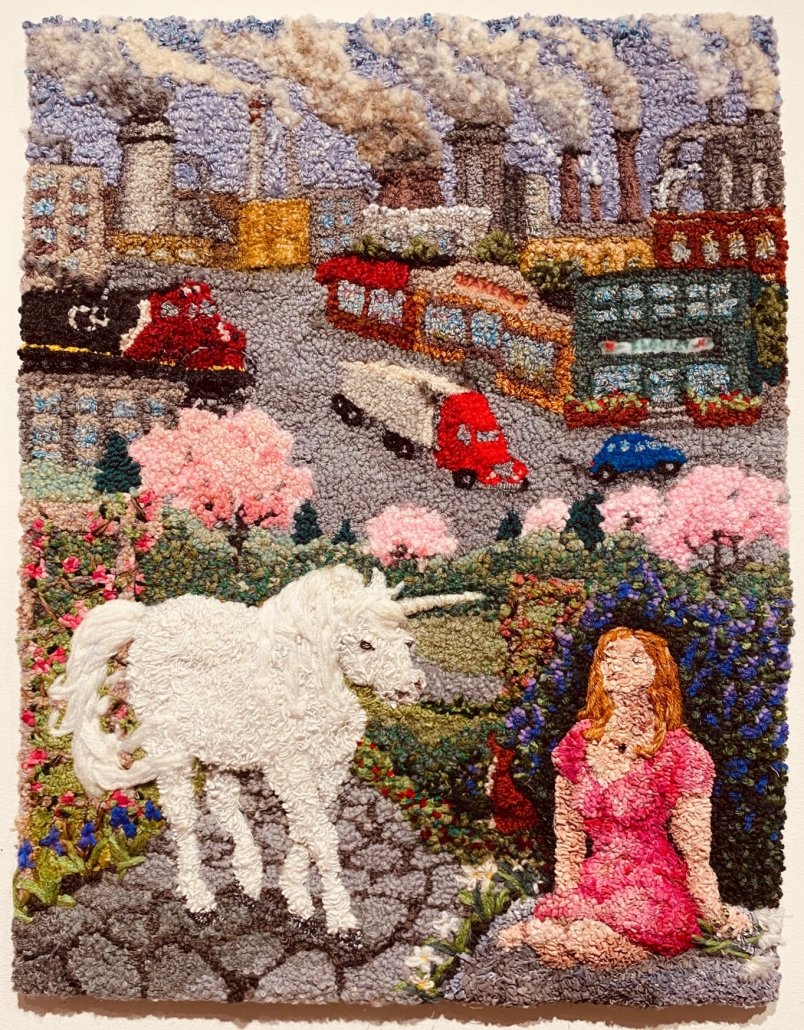

There is a persistently humble quality about hooked rugs. Historically, they are associated with cast-off burlap feed bags, rags, and the thrums, or leftover fibers from the productions of weaving mills. These materials at the dead end of utility signified purposes served, tasks completed, and processes finished. Women of little means were the gleaners of such remnants from factory floors and feedlots. The normal lifespan of a bolt of cloth, from the fancy petticoat to the bottom of the kitchen wash bucket, was prolonged and given a new purpose by the quick hands that collected fabric remains for the handwork needed at home. Often referred to as the “craft of poverty” rug hooking was a necessity rather than a pastime.

In Canada, the establishment of the Grenfell Mission (later Grenfell Industrial) in Newfoundland at the end of the 19c gave rise to a handicraft industry based on rug hooking. There, it was but one of a group of endeavours planned to improve the lives of precariously employed deep sea fishermen. Born again through necessity, hooked rugs made there were an industrialized transformation of what was originally a local aboriginal craft. Under supervision, brilliant colors and innovative designs were abolished, and quality controls instituted. Soon, however, these Grenfell mats began to reflect the creative inspirations and visual intelligence of the artists themselves. Grenfell mats are characterized by unique combinations of mundane objects, local flora and fauna, and designs taken from old book plates. (footnote). Today, such rugs command large prices, and draw the admiring attention of art writers and gallery owners.

In many ways, the career of Calgary fiber artist Sharon Johnston is a microcosm of the history of rug-hooking. As a result of the formative influence of necessity – Johnston’s early life offered few opportunities for an intelligent and creative child – she was raised to ask for little and to “make do”. As she recalls: “We were always hemming bolts of unbleached, unfinished cotton, and we got fabric ends by the pound. We made things out of other things.”

Her maternal grandfather had been a Bernardo child – one of 35,000 young emigres from British orphanages and workhouses that were brought to Canada via a charitable institution founded by the preacher Thomas John Bernardo (1845-1905). One of seven children, her mother grew up in Nelson, British Columbia, and raised her own children there. After high school Sharon (nee Fox), found a job at the Royal Bank in Richmond, B.C. and at age 18 defiantly eloped with Dennis Johnston. For 33 years Dennis and Sharon Johnston managed a farm at Cache Creek with their two daughters Leah and Manda, while Sharon worked at a small jewelry store that was a tourist stop for visitors to the Canadian outback from Europe. Like all intellectually curious people, she sought interesting conversation at every opportunity. The store owners’ son was a student of languages, and Johnston was informally exposed to a wide variety of people from different cultures. She made jewelry, small crafts, painted, and even enrolled in a rug-hooking class, where she was promptly put off by the instructor’s rigid, unimaginative instructional style and narrow view of the craft: “It did not appeal to me. There were way too many rules!”. Like the early hooked rug makers, Johnston had always chosen her own materials from her immediate environment, and created objects from personal inspiration, rather than from pedagogical direction. Naturally, she determined to learn more about the craft of rug hooking by herself: “some photos in a book caught my eye…and reading more about the subject I decided to give it another try.”

Johnston’s most ambitious work to date is the group of 27 heads, collectively titled Of a Common Thread. They were exhibited in a travelling group show titled Womens’ Hands Building a Nation, celebrating the contributions of women to Canada on its 150th anniversary in 1917. Today, they will be part of a solo exhibition at The Collectors’ Gallery of Art opening Saturday, July 24, 2021. Johnston describes them as: “representing different waves of immigration to Canada…we have all come from somewhere to settle this land…(they) are in cloth and yarns using new and old techniques, hence another common thread”. Johnston’s working method encapsulated prior approaches and incorporated some new ones:

“I researched all the countries I included on the internet, in books on national costumes and head dress, as I would only be using heads and a bit of shoulders. I tried to choose a national look for each and sometimes I just played with the look because I liked a certain hat. Then I made quick sketches and saved photos and scans to work from for colours. I saved eyes for shape and colour, and other features for the different nationalities. I then drew out each in the size I wanted and traced those onto the backing fabric. I proceeded to hook and add embellishments to give a more ethnic look to each. Showing the heads spurred me on as an artist and the feedback I received gave me confidence to push the tradition further.”

In this work of multiple elements a thematic and aesthetic unity is achieved. The painterly qualities of each complexion are created through a complex interweaving of color areas and textures. The vibrant lemon yellow of the Sudanese woman’s clothing reflects light by way of strategically placed sections of sepia, cream and buff. On the face, matte sections are indicated with pure black, and highlights with irregular patches of mixed grey, purple and brown to convey both the true undertones of the skin, and the impression of light reflecting from it. Her head is a combination of a profile and three quarters view; while we see the silhouette of her features, we see also both of her eyes. The lifted brows and liquidity of the gaze create an impression of vulnerability and sensitivity. A subtle black outline around the headdress suggests recession into depth, and thus mass and volume. From a small, flat woven mat a personality emerges, and claims her space. The Englishwoman is a feisty, aging rose. The neat blue hat, augmented by a “real” ribbon contrasts with a fair face gently marked by a multitude of age spots, and a small dark mole above her left eyebrow. The area of the chin, and within the boundaries of the naso-labial folds is lightened to suggest emergence from the plane of her cheeks, and she looks out at us with a discerning (if not judgemental) blue eye. In true Johnstonian style, the Inuit woman is nestled within a fluffy white aureole of real fur. The delicate monolid eyes are expressively cast sideways, and her heart shaped lips appear to have parted slightly in response to something she sees. Each of these women is an immigrant, and on the threshold of a strange, new world. These are individuals, but are characterized by their culture of origin. They have converged through force of chance and history, and then again through the creative imagination of their maker

The relationship between rug-hooking and the handwork of women has been well established. For some contemporary artists, the medium’s strong historical associations are subverted to expressive effect. (EMILY URQUHART SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL PUBLISHED JANUARY 27, 2016…a review of an exhibition held at the Canadian Textile Museum in Toronto.) However, Johnston’s work expresses an affiliative and personal feminism which is shaped by her own history, and a ferociously independent turn of mind. She does not readily receive the wisdoms issuing from either end of the political spectrum, and continues to nurture ideas through wisdom of her own hands.

Elizabeth Herbert